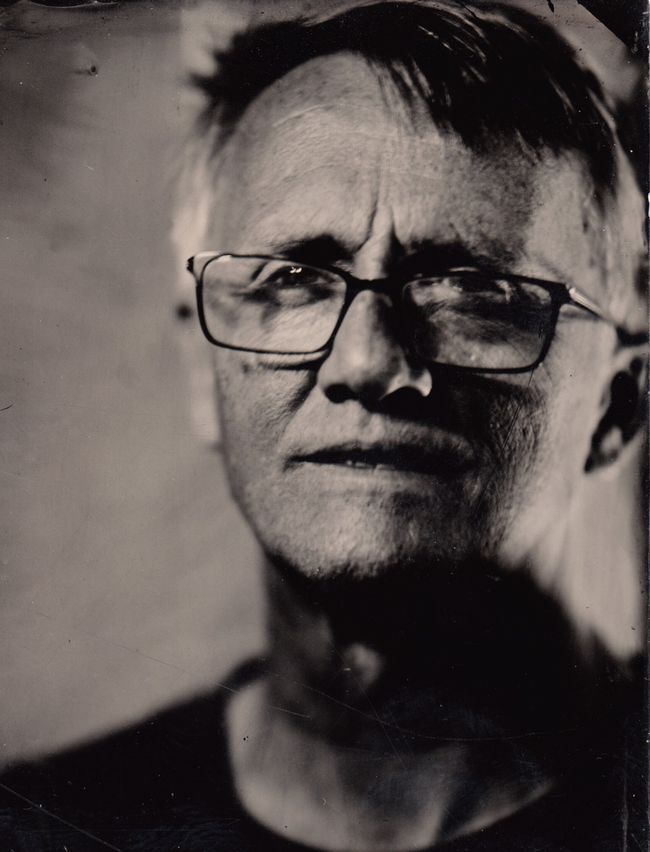

John Hoare, a professional director of photography who has also developed a passion for wet plate photography

An interview with John Hoare, a professional director of photography who has also developed a passion for wet plate photography, an antique photographic technique dating back to the 1850s. John shares how this method contrasts with his high-tech day job, describing the process in detail—using chemicals like collodion and silver nitrate, and working with cumbersome equipment like a Bellows camera. The technique requires long exposure times, creating challenges but also adding a unique, antique aesthetic to his work.

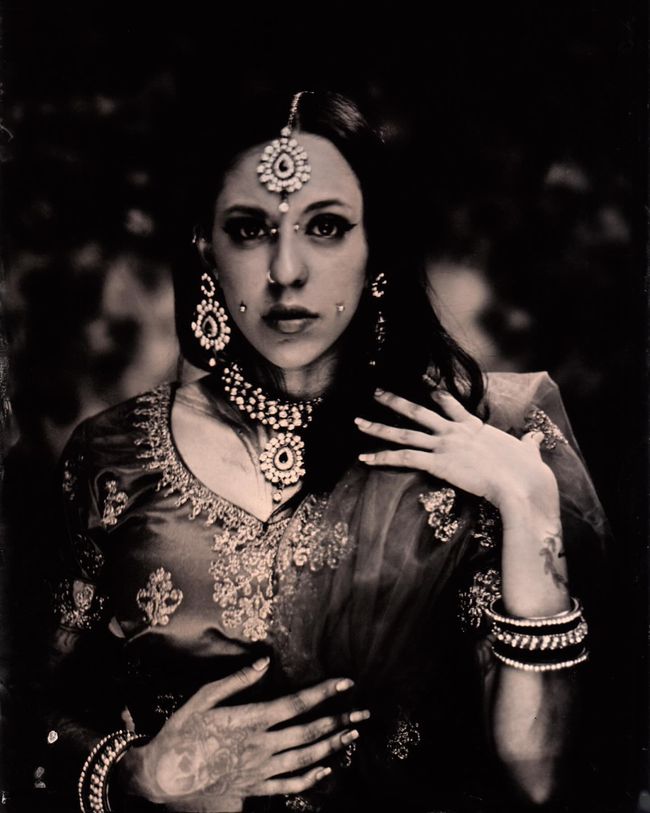

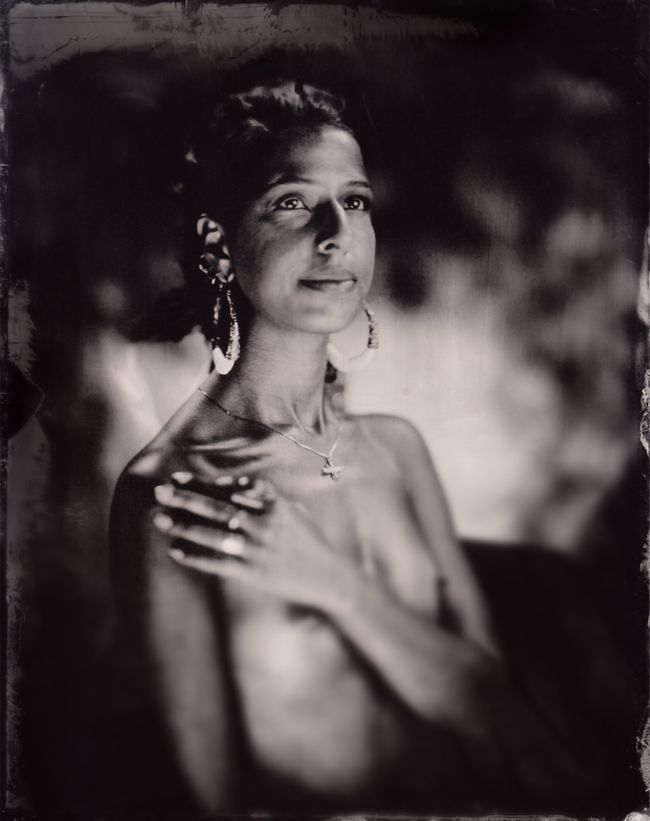

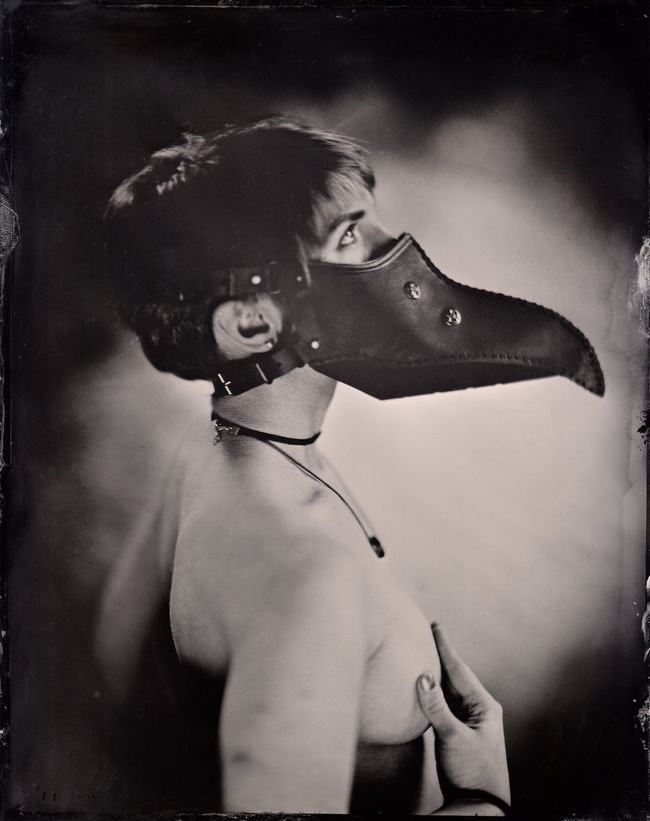

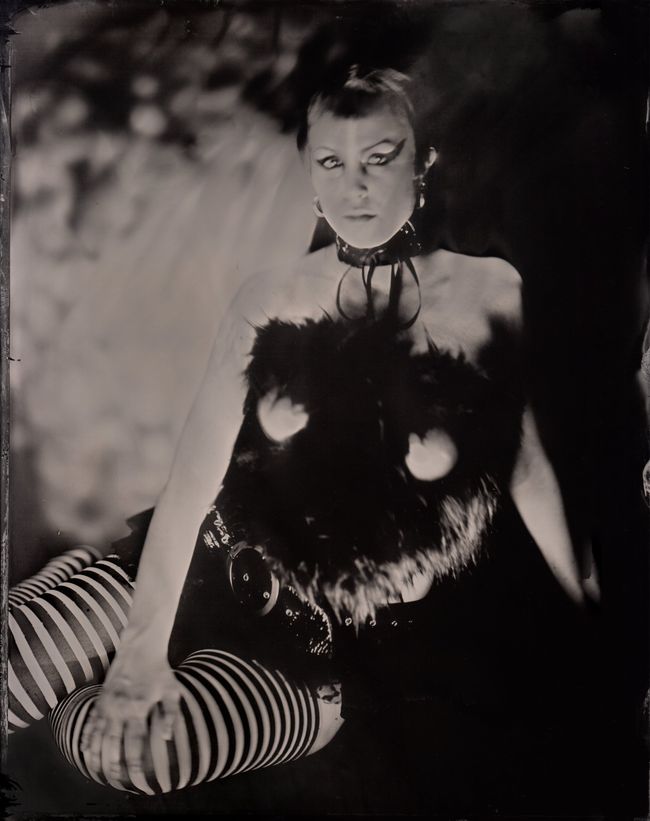

As a side note, all the portraits that appear in this article are of life models that have visited my weekly class at the library. To know more about them you can visit their Instagram page by clicking the photograph.

Rediscovering a Forgotten Art: The Mystique of Wet Plate Photography with John Hoare

In today’s world of instant photography and high-resolution cameras, the digital age offers precision and convenience like never before. However, for some, the allure of older, imperfect processes holds a charm that no megapixel count can replicate. John Hoare, a professional director of photography, has embarked on a journey to revive one of the oldest photographic methods—wet plate collodion photography—and in doing so, he’s found a new form of artistic expression that is steeped in history, mystery, and beauty.

A Step Back in Time

Wet plate collodion photography, first developed in the 1850s, was once the cutting-edge technology of its time. It involved coating a glass or metal plate with chemicals, making it sensitive to light, and then exposing and developing it while still wet. The entire process had to be completed within a narrow timeframe, often just minutes, before the plate dried.

“It’s the complete opposite of what I do in filmmaking,” John reflects. “Digital cameras are fast and reliable. Wet plate photography is slow, messy, and unpredictable. But that’s exactly why I love it.”

The painstaking process begins with preparing a plate by pouring collodion onto its surface, evenly spreading it before submerging it into a bath of silver nitrate. Once light-sensitive, the plate is loaded into a large-format camera and exposed to capture an image. The timing is critical: from coating to exposure to development, the plate must remain wet, or the entire effort will fail. The plate is then developed using a series of chemical baths, a delicate procedure that reveals a ghostly image emerging from what was once a blank surface.

The Mystery of the Image

There is an inherent mystique to wet plate photography that goes beyond its antique origins. The images it produces have a haunting, otherworldly quality—a depth that seems to draw the viewer into another time. Unlike modern images with their crisp perfection, these photographs have streaks, variations, and imperfections that give each plate a unique character.

“It’s like watching a secret unfold before your eyes,” John says. “You never know exactly what the final image will look like. Sometimes, you get subtle chemical stains or uneven textures. But those imperfections aren’t flaws; they’re what make the photograph alive.”

One of the most striking elements of wet plate images is their play with ultraviolet light, which interacts differently with human features compared to modern cameras. Freckles appear more pronounced, light-colored eyes take on an almost translucent glow, and skin tones shift into a realm of rich contrast. The shallow depth of field enhances this mysterious effect, blurring the boundary between sharpness and shadow.

Crafting Portraits with Patience and Precision

John’s backyard studio is a time machine of sorts, filled with the tools and equipment necessary to create these intricate works. A large-format bellows camera, chemical trays, and an improvised darkroom are the cornerstones of his practice. Unlike the quick snapshots of digital photography, creating a wet plate portrait requires patience—both from the photographer and the subject.

“You can’t just snap a photo and move on,” he explains. “The exposure time can last several seconds, so the subject needs to remain perfectly still. There’s a ritualistic quality to the entire process.”

Collaboration plays a key role in John’s artistic vision. He invites his subjects to bring props, garments, or personal items that resonate with them. Together, they craft an image that feels timeless, one steeped in personal meaning and Victorian-era charm.

Lighting is another crucial element, one that John handles with a director’s expertise. He uses a mix of natural and artificial light to sculpt each portrait, ensuring that the model’s features are highlighted in dramatic and flattering ways. Every shadow, reflection, and glimmer contributes to the final ethereal effect.

Beauty in Imperfection

One of the most compelling reasons John is drawn to wet plate photography is its embrace of imperfection. Unlike the polished precision of digital editing, there is no undo button or post-processing magic in this medium. The chemicals, the timing, and the environment all leave their marks on the plate—sometimes in ways that surprise even the most skilled photographer.

“There’s a sense of surrender in this process,” John shares. “You can master the technique, but you can’t control everything. The mistakes are part of the story, and they add to the mystery of the final image.”

Why Wet Plate Photography Matters Today

In a culture driven by immediacy, where photographs are taken, edited, and shared within moments, wet plate photography offers a welcome reprieve. It’s a reminder of the value of time, patience, and hands-on craftsmanship. Each plate is not just a picture—it is an artifact, a tactile piece of history imbued with the labor and soul of its creator.

“There’s something deeply satisfying about making an image entirely with your hands,” John says. “From pouring the collodion to developing the plate, every step is an act of creation. And when you hold the final image, it feels alive in a way that no digital file ever could.”

John Hoare’s work in wet plate photography serves as a bridge between past and present, a testament to the enduring power of imperfection and the timeless allure of mystery. Through his portraits, he captures more than just faces—he immortalizes moments, creating a visual language where flaws become features and every plate tells a story that lingers long after the chemicals have dried.

In an era where clarity and speed dominate, the enigmatic beauty of a wet plate photograph reminds us that sometimes, it’s the unknown, the imperfect, and the unpredictable that leave the deepest impressions.

Attribution (in order of appearance):

John,

Sybil,

Anjie,

Azi,

Charlotte & Bruce,

Morgan,

Marianna,

Noy,

Shardae-Rose,

and Sofia.

These images have been published with the express permission of the respective party, and the owner of the copyright, John Hoare

(https://www.collodion.co.uk/).

The page banner collage was created with photographs taken by Sofia Olarte (above), during her wetplate portrait session with John. You can read more about her in the blog article "Sofia international life model & artist"