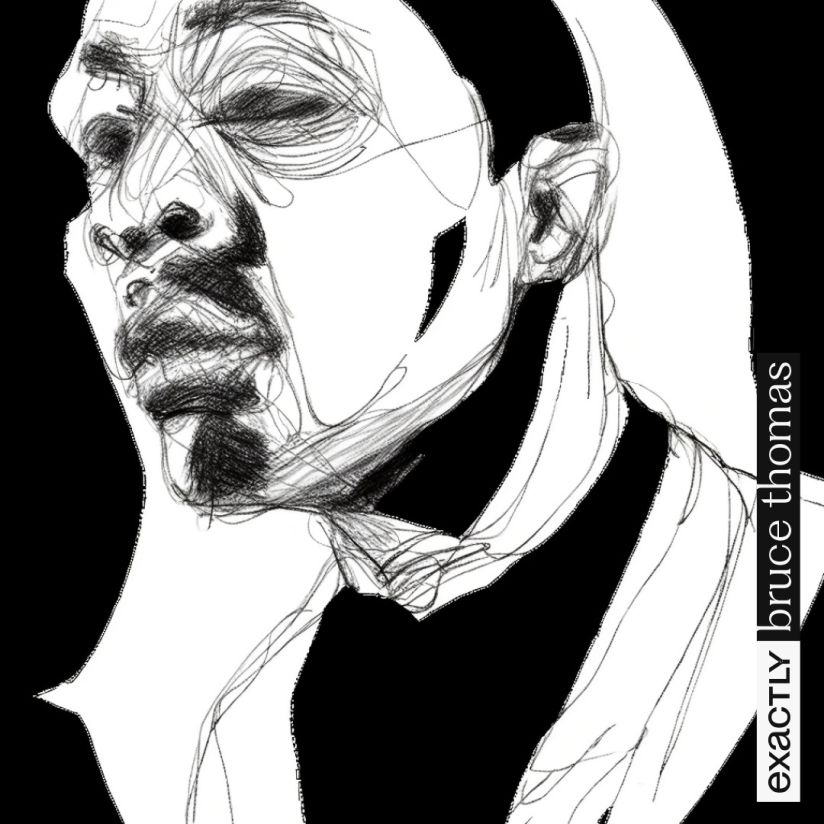

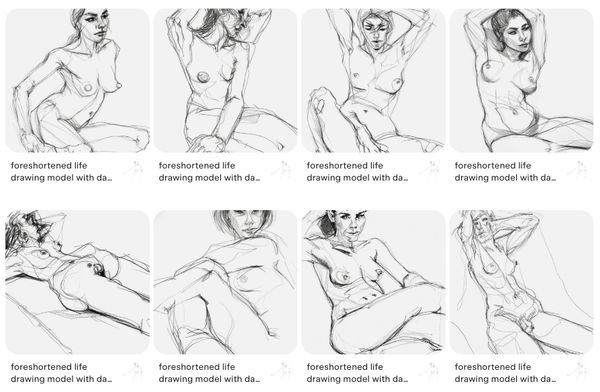

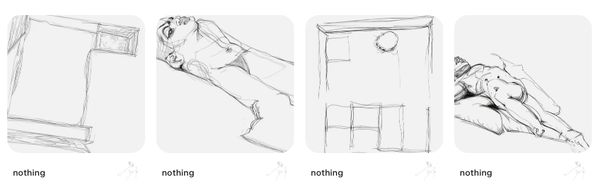

All of these images were generated by artificial intelligence. Each one was created in under 5 seconds and attempts to mimic my style. This is AI-generated art, and it’s quite astounding.

In this experiment, I collected two sets of drawings, each representing a particular style, and uploaded them to a website. The site ingested the original images and analyzed their characteristics—a process known as machine learning. Each image is processed through an interconnected web of mathematical equations, most commonly referred to as a neural network (often mistakenly called “the algorithm”). This initial step trains the network to emulate my style.

The learning process took about half an hour per set (I’m not sure exactly, as it happened overnight). The more images you provide, the better the algorithm becomes at predicting your style, though this also increases the computation time. I gave it 10 images per set, which is a relatively small sample. The service I used offers a free tier with limits on the number of images you can train with, while paying customers can upload larger sets.

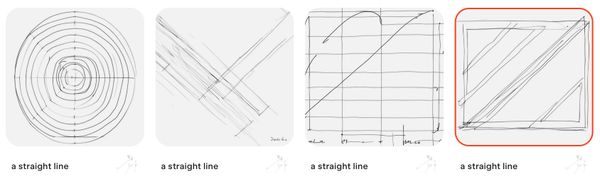

Once the training was complete, the next step was to write a descriptive sentence for something I wanted to generate. Then, with a click of a button, I’d receive four variations of that description in under five seconds, which I could refine until I was satisfied with the result.

At first, I wrote long, elaborate descriptions like “A Victorian woman with white skin wearing a corset and veil, looking sad, with a ghost standing behind her,” or “A close-up of a Victorian woman with ivory skin and a black dress in a very dark birchwood forest at midnight, with a white specter watching from behind, in the style of Aubrey Beardsley, with heavy black shadows and finely detailed clothing.”

But soon, ADHD took over, and my prompts became much simpler. I went from “Drawing of a naked man, white paper, black line, minimal, detailed face” to “Anything you want” and “Spider, foreshortened,” and eventually to my favorites: “Something ugly,” “Nothing,” and “A straight line.”

The platform I used for this experiment is EXACTLY.AI. While other services, like imagine.art, produce better imagery (using the sophisticated MidJourney AI backend), I chose EXACTLY.AI because it allows for style transfer based on my input images and offers a modest free trial.

what is style transfer?

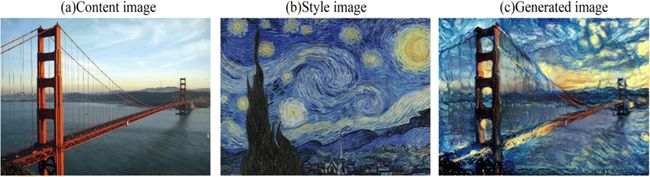

EXACTLY.AI is an example of an AI concept known as style transfer. Essentially, it takes an input image and renders it in another artist’s style. For example, you can upload a photo of Golden Gate Bridge, choose Vincent Van Gogh’s style, and the AI will generate an image that looks like a Van Gogh painting—all in about 6 seconds.

I was fascinated to see my work interpreted in this way. Some of the generated images were surprisingly good, and I’d recommend trying it out for yourself. But after a while, the novelty wears off. You can create 25 drawings in a quarter of an hour, yet there’s no real satisfaction in the process. The ease of creating art this way eventually becomes frustrating. Furthermore, there’s no point of reference to measure the results against in terms of its origin.

For me, the satisfaction of drawing comes from the difficulty. Observing the world in all its three-dimensional complexity and collapsing it into a two-dimensional space is a challenge. Quieting the inner critic and silencing the noise of the mind is difficult. Making my hand obey my eye is difficult. (Not as difficult as convincing Phillip to use larger paper, though—that's practically impossible.) Appreciating how my craft measures up against other seasoned artists is difficult.

Seeing a new artist's tiny smile when they realize they've improved is priceless. I draw for these reasons, not for the finished work. It’s the hours that pass in a blink that I’m addicted to. It’s the intimate attention I give to the subject, who is both safe and vulnerable. It’s the act of returning to draw a human figure, week after week.

In any given drawing session of two hours, I usually manage only about ten sketches. Of those, sometimes there’s only one that I like. The others often sit in a pile for months, until one day I critically review them, selecting the ones that have some emotional weight or subjective significance. The rest are discarded, or recycled if the paper is particularly nice.

Beauty is not an inherent quality of the model; it is a declaration I make about them. It’s a gift I’m compelled to give, something I seek to capture, and it resides in everyone we encounter. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

In conclusion, here’s why I believe AI can’t truly draw. Imagine that as an artist, you could study all the art ever created, and you had a perfect library of every photograph and subject ever captured. You could replicate any art style perfectly, but the only way to manifest your artwork was by stitching tiny threads of colored yarn on an incredibly dense tapestry canvas. You could mix any styles you’ve learned—say, Impressionism and Cubism—but would this create an original style? I’m inclined to say no. It’s simply a mashup of things that already exist in history.

Something original, by definition, must be distinct from everything that came before. It’s unpredictable. Hypothetically, if Pablo Picasso had never been born, Cubism would not exist. This means that all the knowledge of art we have today would be missing a chapter on Cubism. Similarly, if Vincent Van Gogh had never existed, his distinctive approach to form would not exist either.

This is where the contemporary fear of AI art falls flat.

The images it generates lack originality. The combination of subjects and styles that AI produces can only remix things that already exist. AI doesn’t have accidents or mistakes—it doesn’t stumble upon new ideas by chance. While computers can generate random responses, they do so predictably, not by true accident. And I believe that randomness, that element of surprise, is essential to creativity. It is human to err.